Credo Quia Absurdum Est

Yes, I know, it’s a misquote. So is “play it again, Sam” but that doesn’t stop anyone. As a good old movie once said, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend”.

When dealing with quotes, maybe. The rest of the time, not so much. “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem” would be a better fit but I couldn’t find the Latin for that. I don’t actually know Latin; one of my many shortcomings.

Jon Stewart recently had occasion to comment on one of the many silly things Bill O’Reilly has said:

That may force you to endure an ad or two; apologies. The short version is that O’Reilly, in a discussion with a representative of American Atheists, states that Christianity is not a religion; it is a philosophy. Stewart takes him to task on this in his typical amusing way.

The first thing we need to observe here is that O’Reilly is simply not this dumb. Not the greatest source in the world I know, but still. O’Reilly is not a journalist; he’s an entertainer. (The same, of course, is true of Stewart, but while I don’t watch his show I’m pretty sure he’s up front about his work being comedy, what with it being on Comedy Central and all). O’Reilly says things deliberately intended to be provocative and start heated arguments. On the internet we call these people “trolls”; on television we pay them ungodly amounts of money. But that’s another rant.

The incident has incited some discussion on the difference between religion and philosophy in my local circles, so here’s my take on it.

The Main Attraction

This one goes first because it’s a deal-breaker: as far as I’m concerned if there’s no god, gods or other supernatural entities involved, it’s not a religion. If there are, then it is, making the involvement of a deity or such both necessary and sufficient to label a belief system as a religion. I expect to be called out on that but that’s why we’re here. And rather than try to defend it here I’m going to show how the following criteria all fit into this one.

Consider the Source

The central tenets of religions come from some kind of revelation. While there is a principle of “general revelation” the core beliefs are likely to come from an individual or group who (it says here) have received some kind of special communication from a supernatural entity of some kind. Nothing like this will be the case in a school of philosophy. However impressed we may be with Kant or Confucius or Rand (work with me here) we don’t try to claim that their writings were divinely inspired. This, of course, gets us back to the whole “supernatural entity” requirement, as we obviously need some otherworldly source to bestow enlightenment upon the first master(s).

Note that this doesn’t mean that the religion’s adherents must believe the central tenets are the literal word of the patron entity. It is only necessary to accept the claim that said tenets were divinely inspired. Per a 2011 Gallup poll, 49% of Americans believe the Bible was divinely inspired but is not to be taken literally. 30% (which is around 100 million people) think it’s the literal word of god. Of course, declaring your tenets to be infallible does confer certain advantages.

No Complaints Department

Philosophy and (even more so) science thrive on dissent, at least when practiced properly. We can all recount numerous examples of individuals or groups attempting to quash inquiry on various issues but this is recognized as bad behavior and usually comes to an end fairly soon. (As such things are measured — a philosophical or scientific “movement” that dies out after only twenty or thirty years has practically suffered a crib death.) When we live up to our ideals, everything is open to question and re-examination.

This is much less true of religions. Some religions or sects are less dogmatic than others but even in the most liberal of them there will be some set of beliefs that are simply not to be questioned. After all, they are (purportedly) divinely inspired and transmitted to the lay membership by people who have had special experiences that can’t be questioned. As Stewart notes in the video, you can’t be a Christian (of any type) if you don’t believe in the divinity of Christ. You can question whether Christ was crucified through the hands or through the wrists (at least I think you can; as far as I know there’s no dogma on that), but you’d better believe he died on the cross for mankind’s sins if you want to stay in the church. Dissent is limited to minor issues, or (maybe) how to apply church doctrine to real-world issues. The doctrine itself is off-limits. And once you’ve got your people convinced that they’re possessed of an indisputable truth, you can give them something else to do.

Spread The Word

If you were absolutely certain that you knew the secrets of life, maybe even how to earn an eternal afterlife in a paradise, wouldn’t you want to share that? Maybe feel you had a moral obligation to? Of course you would. Divine knowledge, at least that part of it distributed to the lay members, needs to be spread. Religions overwhelmingly tend be evangelical. The most successful religion I know of that is rarely evangelical is Sikhism. It is the world’s fifth most popular religion but a) it is almost entirely concentrated in one part of India and b) at roughly 25 million adherents, it has about 6% of the adherents of the next most popular religion, Buddhism (about 380 million adherents). (I haven’t looked but I’d be willing to bet that figure for Buddhism is counting a lot of Tibetan Buddhists. Tibetan Buddhism a) is as evangelical as all get-out and b) contains the least actual Buddhist content of any strain of Buddhism.)

Philosophy isn’t terribly evangelical. Sure, philosophers love to talk about their work but generally only to other philosophers or people interested in philosophy. Partly this is because philosophers are painfully aware of how often they, as a group, have been wrong; as previously mentioned, the field runs largely on doubt. But I suspect the main reason is because even if they did, say, put together a warped version of The Watchtower based on Kantian morality, who would understand it?

So, You Might Be A Theist If…

…you’re part of an organized belief system that’s allegedly based on knowledge bestowed by one or more supernatural beings that you’re supposed to disseminate without question.

Can you treat a religion philosophically? Sure. You can be philosophical about anything.

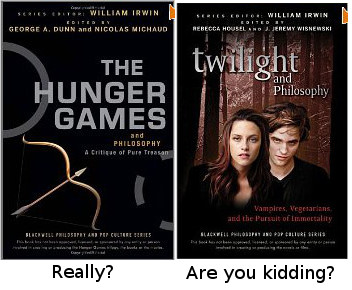

I tried to find “Philosophy of 50 Shades of Grey” but I guess that’s just too silly. Or maybe it’s not out yet.

But as Stewart said, a philosophical treatment of a religion is not, itself, the religion.

But Wait…

…I hear you say…

…”aren’t there non-theistic or even atheistic groups that do the same things?”

Sure there are. I threw out Ayn Rand’s name up there for a reason. Following her death the Objectivist (or as I like to think of it Objectionablist) movement jumped right off the slippery slope in creating a group as fundamentalist as any religion. There were big fights over which one of Rand’s ex-lovers got to speak for her after her death, lists of “authorized” Objectivist writings, lists of “forbidden” writings and reading any of those or questioning the “leaders” got you thrown out of the movement. I haven’t seen this term used in a while, probably because of its similarity to a currently popular operating system, but on the net we used to call Objectivist devotees “Randroids”. Soviet Communism was the same. Theists love to tar and feather atheists with Stalin’s atrocities but he didn’t do anything theistic autocrats hadn’t been doing for ages. Chin Shih Huang-ti did the same things and he not only believed in gods, he thought he was one.

Fanaticism does not make a belief system a religion, but it can make one as dogmatic and irrational as any religion. So what you should really take away from all this is:

If you find the people you share beliefs with have their own letterhead, RUN.

Recent Comments